SOLID Principles In Practice With Python And UML Examples in 2025

\ Let’s be real: most developers nod politely when SOLID comes up, then continue writing 500-line classes that smell worse than week-old fried eggs.

Here’s the thing: SOLID isn’t about pleasing your CS professor. It’s about writing code that your future self won’t want to rage-quit from after a single bugfix. Bad code means frustration, late nights, and way too much coffee.

SOLID is a language that senior devs use to communicate across years of maintenance. When you see it in a project, you don’t need to crawl line by line like some code archaeologist digging through ruins. Instead, you can predict the system’s behavior, understand responsibilities, and trust that classes aren’t hiding surprises like a clown in a sewer drain. Follow it, and you can read code like a map. Ignore it, and you're wandering blind through spaghetti caves.

What is SOLID (for the two people who missed the party)?

SOLID is an acronym for five object-oriented design principles coined by Uncle Bob Martin back when 2000s were still a thing:

- S — Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

- O — Open–Closed Principle (OCP)

- L — Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

- I — Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

- D — Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Each principle is simple in words, but game-changing in practice. Let’s walk through them with Python and UML examples, and see why your future code reviewers will thank you.

\

🪓 Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

One job, one class. Don’t be that developer who mixes logging, DB writes, and business logic in one method.

Why it matters

If a class does too many things, every change risks breaking unrelated behavior. It’s like wiring your home’s electricity, plumbing, and gas through the same pipe - one adjustment and the whole house either floods, burns, or explodes.

Bad Example

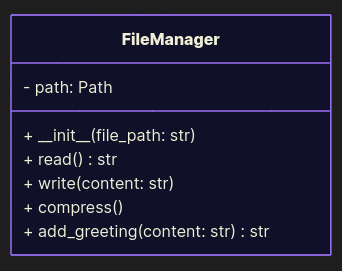

Here’s a FileManager class that thinks it’s Batman: reads files, writes them, compresses them, and even appends greetings:

from pathlib import Path from zipfile import ZipFile class FileManager: def __init__(self, file_path: str): self.path = Path(file_path) def read(self) -> str: return self.path.read_text('utf-8') def write(self, content: str): self.path.write_text(content, 'utf-8') def compress(self): with ZipFile(self.path.with_suffix('.zip'), mode='w') as file: file.write(self.path) def add_greeting(self, content: str) -> str: return content + '\nHello world!' if __name__ == '__main__': file_path = 'data.txt' file_manager = FileManager(file_path) content = file_manager.add_greeting(file_manager.read()) file_manager.write(content) file_manager.compress()

What’s wrong?

Although the usage looks easy, every time you need to tweak compression, you risk breaking file writing. Change greetings? Oops, now compression fails.

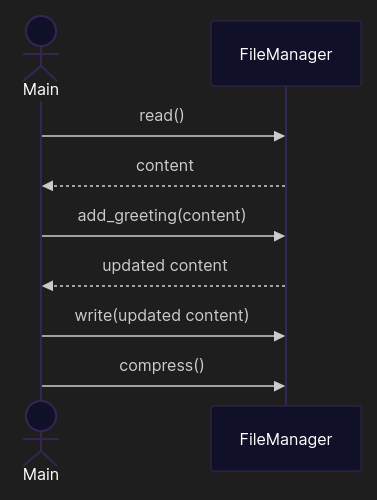

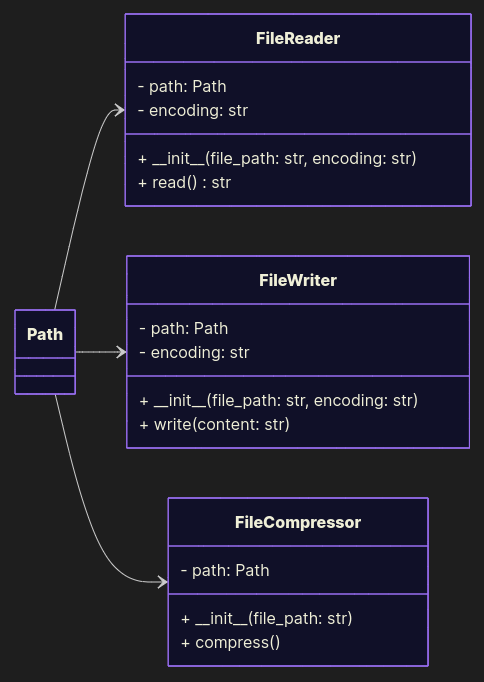

Good Example

Split responsibilities. Each class does one job, cleanly.

from pathlib import Path from zipfile import ZipFile DEFAULT_ENCODING = 'utf-8' class FileReader: def __init__(self, file_path: Path, encoding: str = DEFAULT_ENCODING): self.path = file_path self.encoding = encoding def read(self) -> str: return self.path.read_text(self.encoding) class FileWriter: def __init__(self, file_path: Path, encoding: str = DEFAULT_ENCODING): self.path = file_path self.encoding = encoding def write(self, content: str): self.path.write_text(content, self.encoding) class FileCompressor: def __init__(self, file_path: Path): self.path = file_path def compress(self): with ZipFile(self.path.with_suffix('.zip'), mode='w') as file: file.write(self.path) def add_greeting(self, content: str) -> str: return content + '\nHello world!' if __name__ == '__main__': file_path = Path('data.txt') content = FileReader(file_path).read() FileWriter(file_path).write(add_greeting(content)) FileCompressor(file_path).compress()

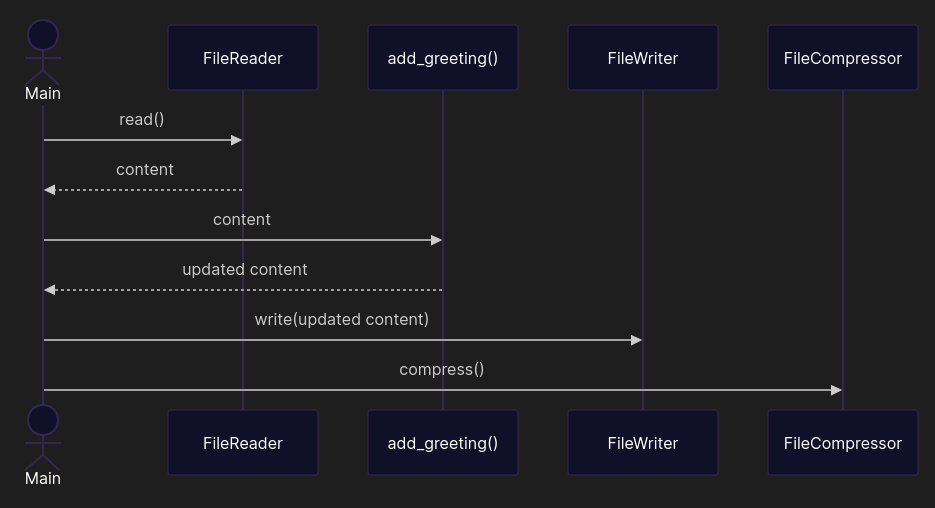

Although the call diagram looks a little trickier, now you can modify compression without touching greetings. Future you approves.

\

🧩 Open–Closed Principle (OCP)

Code should be open for extension, closed for modification. Like Netflix - adding new shows without rewriting the entire app.

Why it matters

If every new feature forces you to edit the same class, your code becomes a fragile Jenga tower. Add one more method, and boom - production outage.

Bad Example

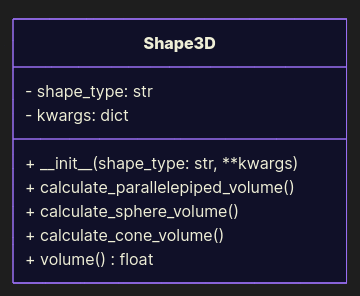

The classic “God class of geometry”:

from math import pi class Shape3D: def __init__(self, shape_type: str, **kwargs): self.shape_type = shape_type self.kwargs = kwargs def calculate_parallelepiped_volume(self): return self.kwargs['w'] * self.kwargs['h'] * self.kwargs['l'] def calculate_sphere_volume(self): return 3 / 4 * pi * self.kwargs['r'] ** 3 def calculate_cone_volume(self): return 1 / 3 * pi * self.kwargs['r'] ** 2 * self.kwargs['h'] def volume(self) -> float: if self.shape_type == 'parallelepiped': return self.calculate_parallelepiped_volume() if self.shape_type == 'sphere': return self.calculate_sphere_volume() if self.shape_type == 'cone': return self.calculate_cone_volume() # Add more ifs forever raise ValueError if __name__ == '__main__': print(Shape3D('parallelepiped', w=1.0, h=2.0, l=3.0).volume()) print(Shape3D('sphere', r=3.5).volume()) print(Shape3D('cone', r=3.5, h=2.0).volume()) Every time you add a new shape, you hack this class. Here, we are not extending; we are modifying. This violates OCP.

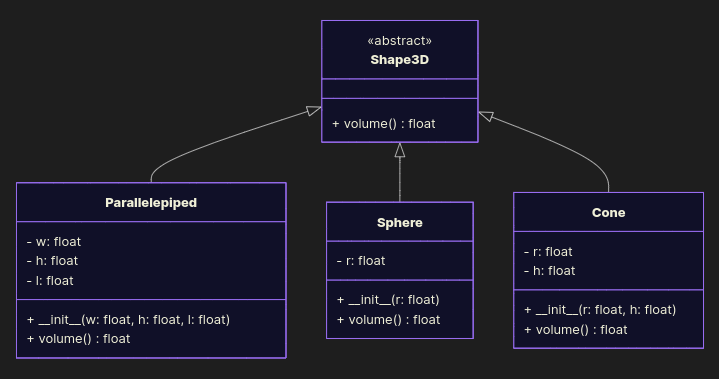

Good Example

Make a common base class, extend it with new shapes.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod from math import pi class Shape3D(ABC): @abstractmethod def volume(self) -> float: raise NotImplementedError class Parallelepiped(Shape3D): def __init__(self, w: float, h: float, l: float): self.w, self.h, self.l = w, h, l def volume(self): return self.w * self.h * self.l class Sphere(Shape3D): def __init__(self, r: float): self.r = r def volume(self): return 3 / 4 * pi * self.r ** 3 class Cone(Shape3D): def __init__(self, r: float, h: float): self.r, self.h = r, h def volume(self): return 1 / 3 * pi * self.r ** 2 * self.h if __name__ == '__main__': print(Parallelepiped(w=1.0, h=2.0, l=3.0).volume()) print(Sphere(r=3.5).volume()) print(Cone(r=3.5, h=2.0).volume()) Want a Torus? Just new subclass. No if-hell required, no edits of old code. Clean. Extensible. Chef’s kiss.

\

🤔 Another Discussable Example of OCP Violation

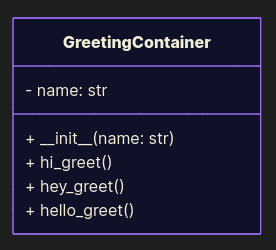

Here’s a class that offers multiple hard-coded greeting methods:

class GreetingContainer: def __init__(self, name: str): self.name = name def hi_greet(self): print("Hi, " + self.name) def hey_greet(self): print("Hey, " + self.name) def hello_greet(self): print("Hello, " + self.name) At first glance this looks fine: we’re not deleting or altering existing methods, we’re just adding new ones. Technically, we’re extending the class. But here’s the catch: clients using this class must know exactly which method to call, and the interface keeps bloating. This design is brittle - new greetings mean more methods and more places in the code that have to be aware of them. You can argue it’s not a direct OCP violation, but it drifts into LSP territory: instances of GreetingContainer can’t be treated uniformly, since behavior depends on which method you pick (we will discuss it a little later).

\

🦆 Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

If code expects an object of some type, any subclass should be usable without nasty surprises. A subclass that breaks this promise isn’t an extension - it’s a landmine disguised as a feature.

Why it matters

Subclasses must be replaceable with their children without breaking stuff. Violate this, and you’ll create runtime landmines.

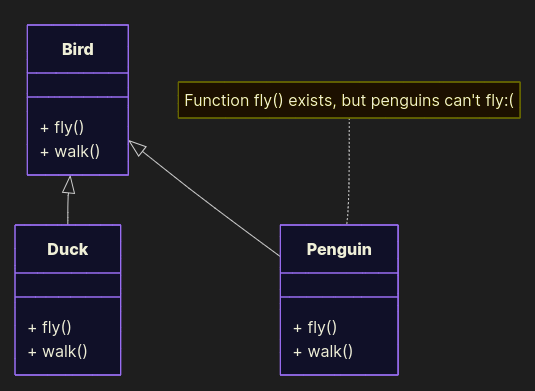

Bad example

class Bird: def fly(self): return "The bird is flying" def walk(self): return "The bird is walking" class Duck(Bird): def fly(self): return "The duck is flying" def walk(self): return "The duck is walking" class Penguin(Bird): def fly(self): raise AttributeError("Penguins cannot fly:(") def walk(self): return "The penguin is walking" Penguins do exist, but they break LSP here. Anywhere you expect a Bird, the substitution fails and the design no longer guarantees consistent behavior.

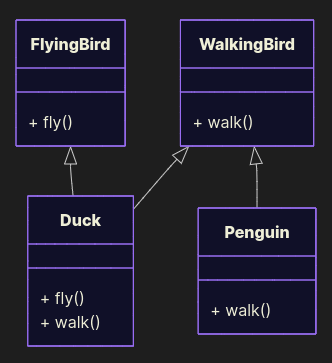

Good example

Split behaviors:

class FlyingBird: def fly(self): return "The bird is flying" class WalkingBird: def walk(self): return "The bird is walking" class Duck(FlyingBird, WalkingBird): def fly(self): return "The duck is flying" def walk(self): return "The duck is walking" class Penguin(WalkingBird): def walk(self): return "The penguin is walking" Now penguins waddle safely. Ducks still fly. Everyone’s happy. No runtime betrayals.

\

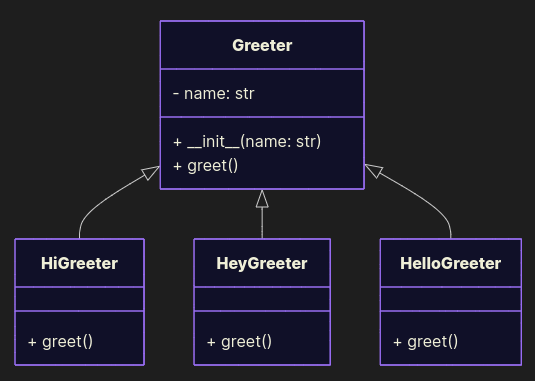

Good Example of a greeter from the OCP topic

Define a base Greeter and extend it with new variants:

class Greeter: def __init__(self, name: str): self.name = name def greet(self): raise NotImplementedError class HiGreeter(Greeter): def greet(self): print("Hi, " + self.name) class HeyGreeter(Greeter): def greet(self): print("Hey, " + self.name) class HelloGreeter(Greeter): def greet(self): print("Hello, " + self.name) This design is cleaner: the interface stays stable (greet()), new greetings are real extensions, and polymorphism works. Clients don’t care how the greeting is produced - they just call greet(). And the real benefit: we can swap one Greeter for another and remain confident the code behaves as expected, without digging into implementation details - because we followed OCP and LSP. That’s the spirit of predictable, maintainable design.

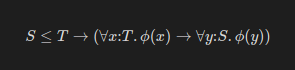

For the nerds, the formal definition of this principle is:

\

🔌 Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

Don’t force a class to implement methods it doesn’t need. Otherwise you’re just padding the code with dead weight.

Why it matters

Clients shouldn’t be forced to implement methods they don’t need. If your interface has eat() and sleep(), but a robot only needs charge(), you’re designing like it’s 1999. Formally: many small, focused interfaces are always better than one bloated interface that forces irrelevant obligations.

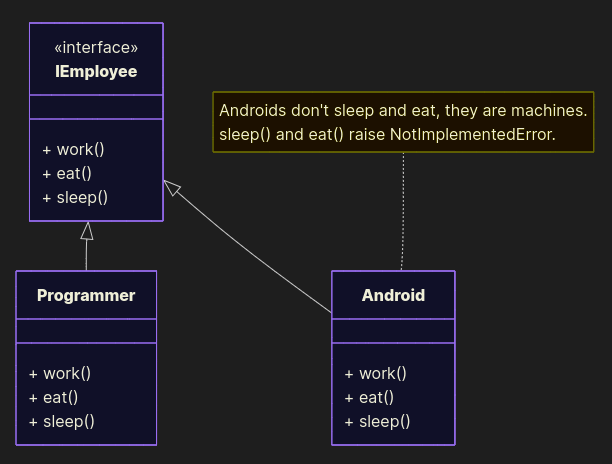

Bad example

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod class IEmployee(ABC): @abstractmethod def work(self): pass @abstractmethod def eat(self): pass @abstractmethod def sleep(self): pass class Programmer(IEmployee): def work(self): print("Programmer programs programs") def eat(self): print("Programmer eats pizza") def sleep(self): print("Programmer falls asleep at 2 AM") class Android(IEmployee): def work(self): print("Android moves boxes") def eat(self): raise NotImplementedError("Android doesn't eat, it's a machine") def sleep(self): raise NotImplementedError("Android doesn't sleep, it's a machine") Good example

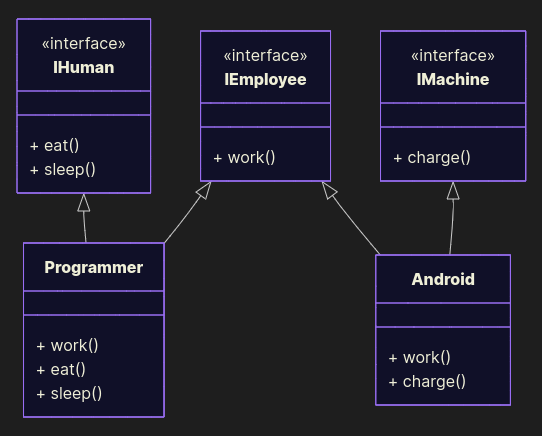

Split interfaces:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod class IEmployee(ABC): @abstractmethod def work(self): pass class IHuman(ABC): @abstractmethod def eat(self): pass @abstractmethod def sleep(self): pass class IMachine: @abstractmethod def charge(self): pass class Programmer(IEmployee, IHuman): def work(self): print("Programmer programs programs") def eat(self): print("Programmer eats pizza") def sleep(self): print("Programmer falls asleep at 2 AM") class Android(IEmployee, IMachine): def work(self): print("Android moves boxes") def charge(self): print("Android charges, wait for 3 hours") Now humans eat, robots charge. No unnecessary code. Interfaces are lean, not bloated.

\

\

🏗 Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Depend on abstractions, not concrete implementations. Otherwise, your code is welded to a single library or vendor like shackles you’ll never escape from.

Why it matters

If your service directly imports boto3, good luck swapping S3 for HDFS, GCS, or even MinIO. From a formal perspective, this creates a tight coupling to a specific implementation rather than an abstraction, which severely limits extensibility and portability. Vendor lock-in = pain, and even a simple architectural decision - like supporting both on-prem HDFS and cloud object storage - suddenly requires massive rewrites.

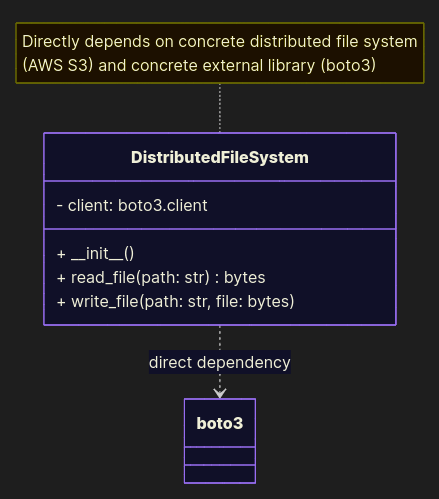

Bad example

import boto3 class DistributedFileSystem: def __init__(self): self.client = boto3.client('s3') def read_file(path: str) -> bytes: data = self.client.get_object(Key=path) return data['Body'].read() def write_file(path: str, file: bytes): self.client.put_object(Body=file, Key=path) Direct AWS dependency. Migrating to another cloud = rewrite.

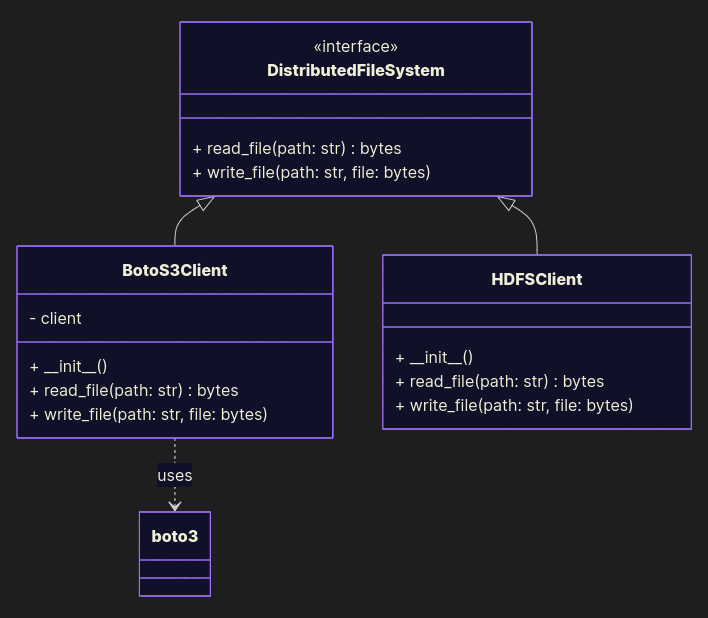

Good example

Abstract it:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod import boto3 class DistributedFileSystem(ABC): @abstractmethod def read_file(path: str) -> bytes: pass @abstractmethod def write_file(path: str, file: bytes): pass class BotoS3Client(DistributedFileSystem): def __init__(self): self.client = boto3.client('s3') def read_file(path: str) -> bytes: data = self.client.get_object(Key=path) return data['Body'].read() def write_file(path: str, file: bytes): self.client.put_object(Body=file, Key=path) class HDFSClient(DistributedFileSystem): ... Now you can switch storage backends without rewriting business logic. Future-proof and vendor-agnostic.

\

Final Thoughts: SOLID ≠ Religion, But It Saves Your Sanity

In 2025, frameworks evolve, clouds change, AI tools promise to “replace us”, but the pain of bad code is eternal.

SOLID isn’t dogma - it’s the difference between code that scales with your project and code nobody wants to work with.

Use SOLID not because Uncle Bob said so, but because your future self (and your team) will actually enjoy working with you.

\

👉 What do you think - are SOLID principles still relevant today, or do you prefer chaos-driven development?

Ayrıca Şunları da Beğenebilirsiniz

Trump-Backed WLFI Plunges 58% – Buyback Plan Announced to Halt Freefall

Son of filmmaker Rob Reiner charged with homicide for death of his parents